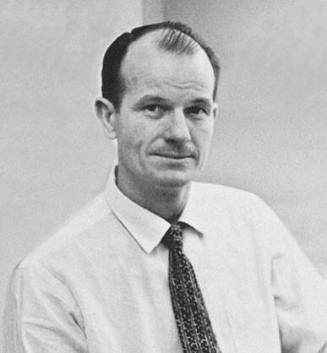

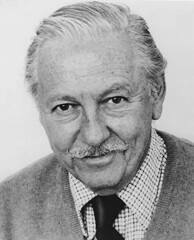

James Swinnerton

1875 - 1974

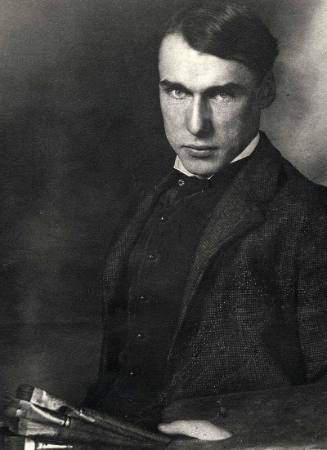

James Guilford Swinnerton was born in Eureka, California, where his father was a judge, a publisher of a weekly paper, and a staunch Republican. Swinnerton studied at the California Art School in San Francisco and went to work for the Examiner in 1892, the first of William Randolph Hearst's newspapers.

In 1887 Hearst had taken over the faltering little Examiner daily, and most of the tricks that became Hearst trademarks were first tried out it it. As a boy, Hearst had become interested in German humor magazines, and while at Harvard he had worked on the Lampoon. For his new paper he wanted drawings and funny pictures, which was where Swinnerton came in.

At first Swinnerton was only a part-time comic artist. It was not until he got back to New York several years later that he was allowed to do comics full time. Because there was still no practical way to use photographs in a newspaper in 1892, all pictorial reporting was done by sketch artists. These artists, Swinnerton included, covered parades, crimes, trials, sports, etc. Swinnerton even had to go out to sketch high school field days. Once, to cover a hotel fire down the coast in Monterey, Hearst hired a train and shipped a whole carload of reporters and artists to cover the event.

The Little Bears, one of the earliest comic art features in an American newspaper, started out as spot drawings to decorate the weather reports, inspired by the bear on the California state flag. His little bears multiplied and began to show up throughout the paper, to be used in promotion stunts. In the mid 1890s, Swinnerton also started turning out large quantities of drawings of his small kids, whom he liked to call tykes. Often the bears and the tykes would get together in parades that stretched across the bottom of a page. They were sometimes referred to editorially as Little Bears and Tykes, but they never appeared in an actual comic strip.

Impressed by the public response to his work, Swinnerton asked for a raise of $2.50 a week, but the editors didn't feel he was worth the extra money. He quit and headed for New York City, where Hearst had bought the New York Journal in 1895. Hearst was involved in circulation wars with Pulitzer's New York World, and most of the many other local dailies, and one of the results of the battles with Pulitzer was the Sunday comic section. Cartoonists were brought back and forth, and for a time The Yellow Kid ran in both the Journal and the World. Finally, Hearst produced a color comics section.

Swinnerton's little bears had always been favorites of Hearst. For the Journal, however, Hearst suggested they be transformed into tigers. Gradually the tigers developed -- from a pantomime strip into a Sunday page complete with dialogue balloons. This version, titled Mr. Jack from 1903 on, dealt with a domesticated tiger that had an office job, a wife, and quite a few lady friends.

During this early trial period, when color comics were expensive and there was some doubt that they would ever catch on enough to turn a profit, Swinnerton continued to do sports cartoons on the side. In 1904, he turned again to tykes and introduced Little Jimmy, a very small boy who shared his first name. Originally titled just Jimmy, the feature began life as a Sunday page. With some lapses, and a hiatus or two, Swinnerton drew the feature until 1958. A daily was added in 1920, at which time the name was changed to Little Jimmy. Swinnerton drew in a simple, uncluttered style, using very little shading and favoring long shots to close-ups.

When comics began to pay off, the Journal decided to let Swinnerton draw them to the exclusion of everything else, which meant the paper needed a new sports cartoonist. Asked to recommend a replacement, Swinnerton said, "There's a fellow named Dorgan out in San Francisco, calls himself Tad. But if your going to get him, you'd better send for his friend, Hype Igoe." The paper sent for the pair, and both became successful sports cartoonists and reporters. Swinnerton once estimated he had helped over three dozen artists get started, ranging from illustrators such a Harold Von Schmidt to newspaper cartoonists such as Darrel McClure and Robert Ripley.

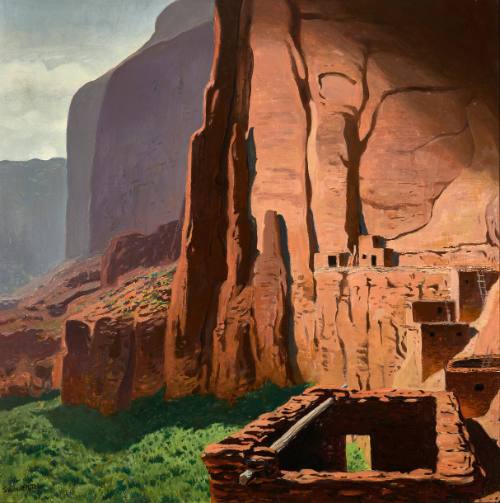

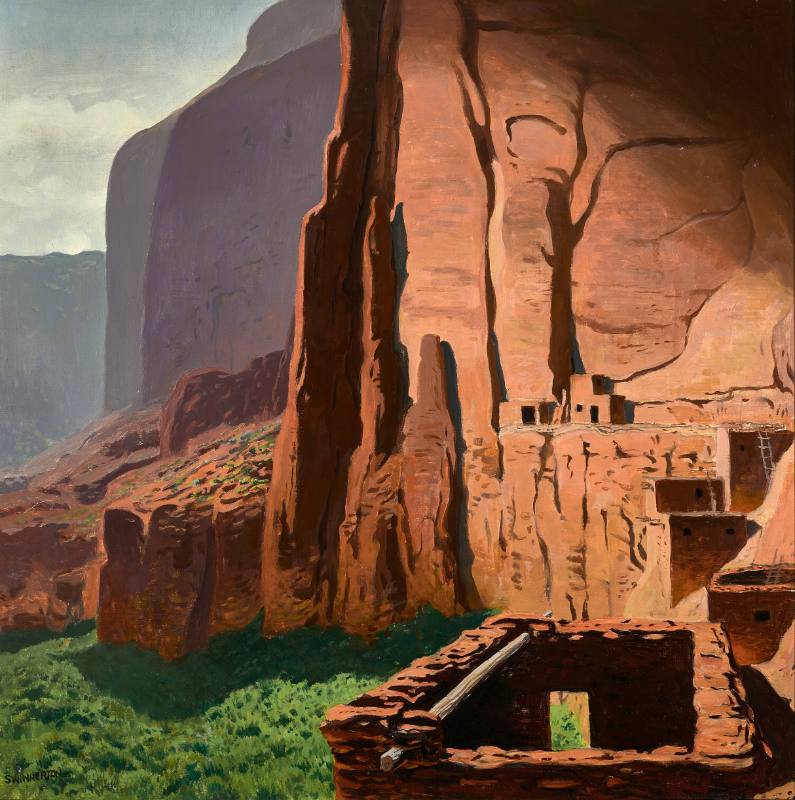

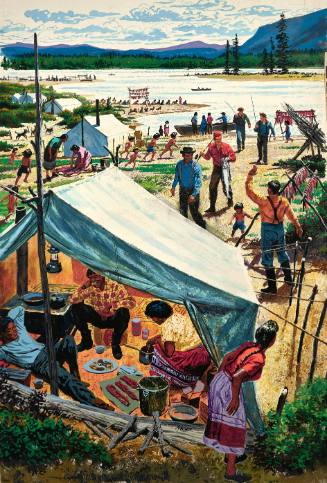

In the first decade of the century, doctors advised Swinnerton that his days were limited. Resigned, he moved to Arizona to await the end. He kept right on waiting, but he didn't die; instead he fell in love with the desert country. He used the scenery in Canyon Kiddies, a handsome color page he drew for Hearst's Good Housekeeping from the early 1920s to the middle of the 1940s. He didn't relocate the diminutive Jimmy to Navajo country until the late 1920s. The Canyon Kiddies also became frequenters of the strip. Swinnerton started painting desert landscapes, too, and remained a painter even after he was no longer able to cartoon.

Source: (Information on the biography above is based on writings from the book, The Encyclopedia of American Comics, edited by Ron Goulart.)

Courtesy of CaliforniaWatercolor.com

Person TypeIndividual