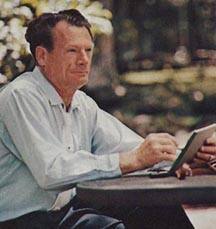

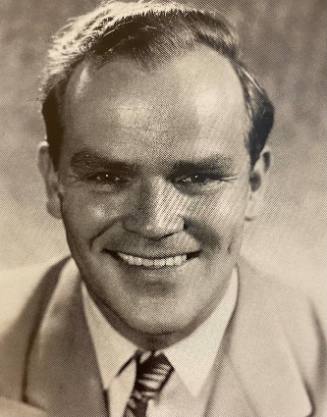

Peter Ellenshaw

1913 - 2007

Ellenshaw’s father died in 1921 and his mother soon married the groundskeeper on an estate in Kent. Ellenshaw’s biological father had family living in Wilton Castle, near Enniscorthy, Ireland, and prior to his father’s death, Peter had been attending a private school in which he was taught, among other things, fine social graces. This ended abruptly as his mother remarried and his family moved into cramped living quarters on the estate his new stepfather tended to. Here, instead of kindly doffing his hat for the ladies, the seven-year old Ellenshaw was enlisted for the purpose of holding the lantern while the latrines were emptied at night.

Recurrent and frequent childhood illnesses left Peter unable to pass the basic entrance exams for grammar school, and at his mother’s suggestion, he became an auto mechanic at 14. Simultaneously, his mother also encouraged him to develop his artistic talent, especially painting and drawing. It was in this manner that Peter managed to keep his floundering self-esteem afloat. “Certainly developed an inferiority complex,” he wrote years later. “Because in England, dirty unskilled work was the lowest rung on the social ladder.”

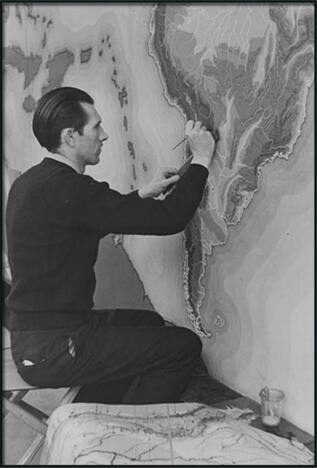

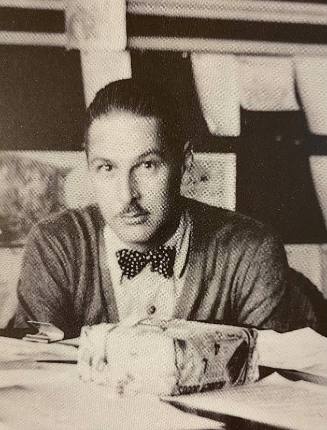

It was around this time that Ellenshaw had a chance meeting with a local artist who would later mentor him not only in painting on canvas, but in painting on glass for the purpose of creating matte backgrounds for film. This man would play a pivotal role in his life in several ways. Percy “Pop” Day, as he was called, was to become a legend in pioneering visual effects for film. Later a recipient of the Order of the British Empire award, Day’s relationship with Ellenshaw became one of mentor-apprentice, as the younger of the two began working alongside the elder doing visual effect work for studios.

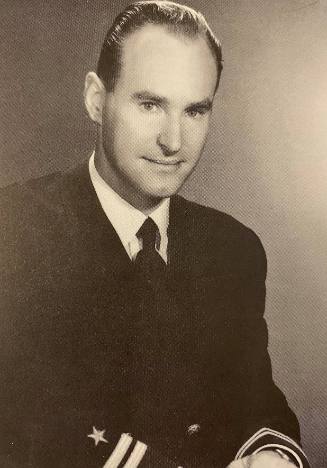

After serving his country as a Royal Air Force pilot in World War II, Ellenshaw returned to work for Mr. Day at the studios. After a brief yearlong stint at MGM, Ellenshaw left in 1947 upon receiving a call to work for Walt Disney Studios on the film, “Treasure Island.” As it turned out, his partnership with Disney would last over thirty years and earn him five Oscar nominations. For his work on “Mary Poppins” in which he recreated scenes of Edwardian London in 102 different mattes, he won an Academy Award.

Walt Disney became Ellenshaw’s mentor and friend, spurring him on continually to perfect his craft and push the creative envelope. “Walt was the dominant figure in my life for all those years,” he wrote years later. “He talked to me as a father would. I cherished our relationship.” However, after Walt Disney passed away in 1968, making movies wasn’t the same anymore. “After Walt was gone, things were different,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I ceased to be as interested in film making.”

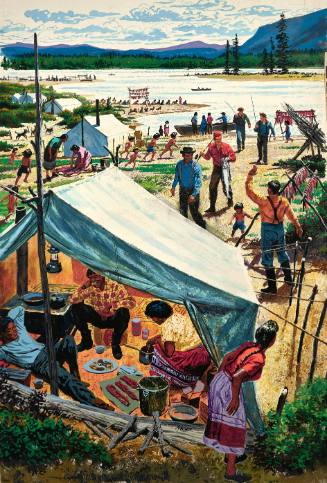

At this time more than ever, Ellenshaw became more engrossed with “his second career” – painting landscapes for the sheer beauty of it. By 1968, it was occupying every possible spare moment as he scurried to keep up with the demand created by galleries and collectors.

Disney’s “The Black Hole” in 1976 was Ellenshaw’s last film for Disney Studios, viewed both as an artistic masterpiece and a cinematic failure. Ellenshaw began to broaden his Hollywood horizons at that point, working on “Superman IV” with son Harrison in 1984.

The work of Peter Ellenshaw is represented in both public and private galleries worldwide. He has been the recipient of numerous honors and awards, including those by the American Film Institute, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Film Institute in Chicago, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the R.W. Norton Art Museum in Shreveport, Louisiana, and the Disney Legends Awards.

Source:

https://www.parkwestgallery.com/artist/peter-ellenshaw/

Person TypeIndividual